First ever mechanical sail taxonomy sets a clear standard for wind propulsion

Inspired by the generational frameworks long used in aviation and autonomous systems, the paper introduces a five-generation model that classifies mechanical sails according to their level of automation, system integration and data intelligence.

“Wind propulsion is no longer a niche or experimental technology,” said Paakkari. “It is evolving into a complex, data-driven system that interacts with the vessel, the route and eventually the wider fleet. A shared definition of the technology generations helps the industry speak the same language about where the technology stands today – and where it is heading next.”

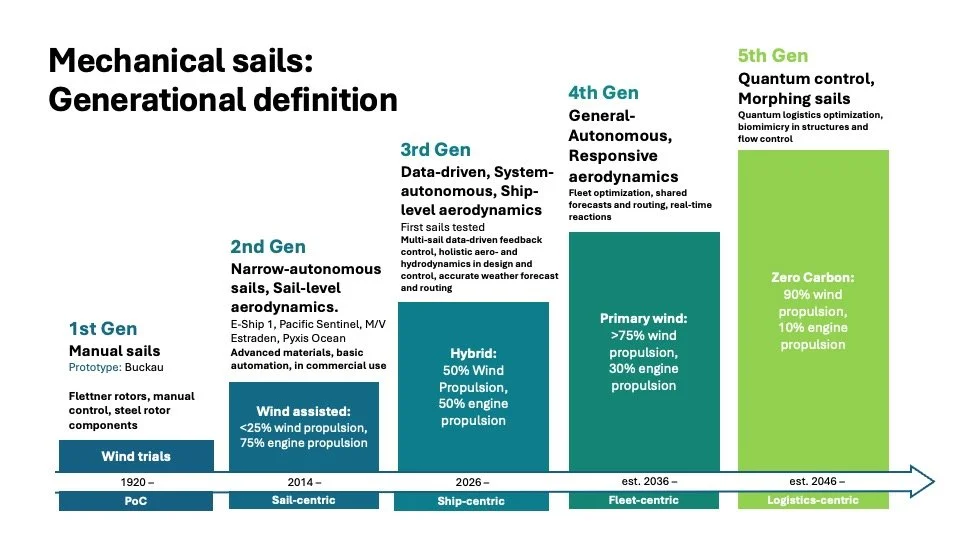

The paper defines five distinct generations of mechanical sails:

• First generation, emerging in the 1920s, when sails were manual and experimental, exemplified by early Flettner rotor prototypes such as Buckau, relying on steel structures and human control.

• Second-generation, sails entering commercial use from around 2014, introduced advanced materials and basic automation at the individual sail level, enabling reliable and predictable fuel savings on operating vessels. These developments, led by wind propulsion developers including Norsepower, have been instrumental in bringing wind-assisted propulsion into mainstream commercial shipping and underpin the rapid growth seen today, paving the way for the industry’s transition.

• Third generation, systems now entering testing and early deployment, where the focus shifts from the sail to the ship, using data-driven, multi-sail control and holistic aerodynamic and hydrodynamic optimisation.

• Fourth generation, concepts extending autonomy to the fleet level, with vessels sharing forecasts and performance data to optimise operations in real time.

• Fifth generation, still theoretical, envision system quantum-enabled optimisation and morphing, biomimetic sails embedded within global logistics networks.

By framing wind propulsion as an evolving engineering discipline rather than a single technology choice, the authors argue that future gains will come not only from hardware improvements, but from software, data integration, and system-level intelligence.

“Introducing technologies from the “eureka”-moment to commercial standards, always goes through generations”, commented Sjöblom. “With the taxonomy we can pinpoint where we are now, how we have gotten here and give a view of our insight in where we are going next. Today we can establish that wind propulsion is a valid solution, suitable for sophisticated vessel integration. It will be interesting to see when - not if - the next generations will take traction.”

The taxonomy also provides a useful reference for regulators, class societies and policymakers as wind-assisted propulsion becomes increasingly embedded in decarbonisation frameworks.

“The industry is at a transition point,” Paakkari added. “As regulations tighten and digitalisation accelerates, understanding the difference between sail-centric and system-centric solutions becomes essential. This taxonomy is intended as a practical tool to support better technical, commercial and regulatory decisions.”

Following the decision taken last week, at the 12th session of the IMO Sub-Committee on Ship Design and Construction, that the IMO will incorporate wind propulsion into its draft safety framework for greenhouse gas (GHG)-reducing technologies, the publication of this white paper is timely. Generational distinction should play a key part of the development of interim guidelines for wind propulsion systems by 2029.

The white paper is available now and is intended to serve as a foundation for further industry dialogue on the future of wind-assisted propulsion.